–

After 54 Years and Thousands of Cardiac Operations Tim Willcox, a Legendary Perfusionist, Retires

–

Tim Willcox retired last month from his job as a clinical perfusionist at Auckland City Hospital.

In March 2025, Tim will be honoured as a ‘Legend in Perfusion’ at the American perfusionists’ association conference in San Diego.

We caught up with Tim last week to reflect on his 54-year career from orderly to chief perfusionist, which took him across the world and through China, India and the Pacific.

How did you get into perfusion?

When I started in 1972 in perfusion it was pure good luck. In 1970 I was 20 years old and desperate for some coin. A friend said, go to Auckland Hospital and get a job as an orderly, it’s easy. I ended up sterilising instruments for the operating theatres at Auckland City Hospital, but I was curious and wanted to have a look at what happened in the operating room. There was an anaesthetist, Basil Hutchinson, who said, ‘Yeah, I can get you in there’. I went in, and the operation was a below knee amputation. They said, ‘Stand at the end of the table and hold this bag.’ They amputated the leg below the knee and dropped it into the bag. It was my first exposure to the operating room.

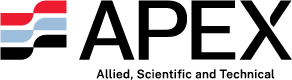

Tim, seated, runs the bypass machine while Sir Brian Barrett-Boyes operates in the 1970s. The anaesthetist is Dr Eve Seelye. Scrub nurse Lizzy Lee.

Why did you stay after that?

Basil said, “we need anaesthetic technicians in Auckland”. There were no ATs at that time apart from two guys, Phillip Ross and Brian Newton, doing the role at Green Lane, but nowhere else in the country. So, Dr Hutch sent me across to be educated by these guys with a view to going back to Auckland. During that year, late ’71 and into ‘72, the chap in charge of the bypass unit, Ron Bentley, had a falling out with the Sid Yarrow, who was the first perfusionist in NZ and HOD. Sid was a slightly cantankerous guy and my boss for many years. Ron left and took a whole bunch of people with him and again, two anaesthetists, Basil Fergus, and Eve Seelye said, ‘you should apply’.

Did they give you much training?

It was all on the job training; perfusion had only started in NZ in 1958. The physiology techs did a Diploma of Physiology, so I did that as well. We were using oxygenators on the heart lung machine that were called Kay-Cross Disc Oxygenators. I would be the only perfusionist in the world still practicing who had used one of those. The oxygenators do the work of the lung, when the heart is on bypass. They were open systems. A long glass tube with 144 stainless steel discs that rotated through a pool of blood and exposed a film of blood to oxygen to create the gas exchange. At the end of the operation, we took the thing to bits, scrubbed 144 discs, coated the discs with petroleum spirit, coating the glass with antifoam.

Did you enjoy those early years on the job?

I was fizzing. Green Lane was a small niche team, there were two operating rooms and every Friday afternoon there was what we would now call a multi-disciplinary team meeting – cardiologists, surgeons, anaesthetists, perfusionists. Cases were discussed for the following week and clinicians did presentations. At Green Lane we were working with Sir Brian Barrett-Boyes, one of the pre-eminent world heart surgeons, in a team which is pumping out research all the time. The research looked at whole body oxygen uptake during heart surgery, and stuff like that. So even junior perfusionists were exposed to that.

For example, they were measuring temperature changes in all parts of the body, and we would put small needles into muscle, skin, and all over the body. When we cooled these patients, usually to 25 degrees from 37, we would look at the way the perfusion affected temperature throughout the body. There were a lot of investigations into oxygen uptake during cardio-pulmonary bypass. As Barrett-Boyes was innovating profound hypothermia in babies – surface cooling them right down to 25C, a raft of other related studies was going on.

Tim’s last case in 2024 with Mr Amul Sibal at Auckland City Hospital.

How did you start getting into research?

In 1980, Dr Ed Harris, who was in charge of the physiology department and who featured at Christmas parties riding his bike backwards, was a great mentor, and he really stimulated me to get into research.

At the time, we re-used everything. The tubing packs that make up the circuit for the heart lung machine we made from bulk tubing. No one in the world was doing that when we were doing it, but we had the facilities to do it. We did this all the way up until 2003, when we relocated to Auckland.

There was scant health and safety back then, we had two ethylene oxide gas sterilisers in the unit, as the bulk of our stuff had to be gas sterilised. There was a big cylinder of sterethox, a mixture of ethylene oxide; a lethal, odourless gas. The plumbing into the sterilizer was slightly dodgy. There was an engineer called Jimmy who came up and gave us a blow torch. He told us to go round the joints on the gas sterilizer and “if the flames go blue, you’ve got a leak, and you should probably tighten it up”. We were exposed to this stuff all the time.

The tubing packs of polyvinyl fluoride tubing which made up the circuits, we would gas sterilize and leave on the shelf in the next room for three days, and then use them on the heart lung machine. Ed Harris said, ‘Look, we should investigate how effective the gas elutes and if it gets into the patient?” And we measured levels of ethylene oxide in patients, and that was my first publication. The findings were that there were not insignificant amounts of ethylene oxide in patients’ blood detected by gas liquid chromatography after bypass. As a result, we extended aeration time. It was my first publication in 1980, and it was pretty rudimentary, but I was hooked.

43 publications on your CV. How did you fit it in?

The research really took off when Dr Simon Mitchell came across to Green Lane to do his PhD. He was using open heart surgery patients as an injury model for dive medicine in terms of air embolism. After open heart surgery, microscopic bubbles are released from the heart before it is closed, which go around the body and some go to the brain. Gaseous microair can subtly injure a patient’s brain. Dive injury is a similar mechanism. He was using lidocaine to see whether this would be neuroprotective.

It was during those experiments we found the oxygenator (in the first photo above), a membrane oxygenator, and at the time a world leading brand’s device; a bubble generator. We were doing the operation, and there was no reason for any emboli in the middle of the operation, Simon was measuring bubbles going up the carotid artery with ultrasound, and telling me, ‘Something is going off. It is to do with the level in your reservoir.’ I was saying, ‘Simon it can’t be, we are three times over the minimum level.’ So, we took the oxygenator into the lab, tested it with ultrasound and lo and behold, there was a fountaining effect in this device. We did this after the day’s work had finished, staying till 10 or 11 o’clock at night, night after night.

What happened after this experiment?

The company flew us out to the States because we were about to publish. They ran their own research, which showed no bubble count, but they had “inadvertently” promulgated the reference data, not the test data, while they made a new device. It was very controversial; we were pretty naïve. We published that, and it led to a stream of publications in that area. It was world leading stuff. We collaborated with some guys at Wake Forest University – Dr David Stump, a neuropsychologist, and Tim Jones, now a paediatric surgeon in the UK, and others. We found venous bubble gas issues in all devices. This, and other researchers who got into this, forced change in equipment design.

As a result of all the 10-15 years’ work, and publications by us and others, the industry completely refocused the design of oxygenators to become much more efficient in micro air removal. We also travelled the globe talking and teaching on these issues.

Looking back on your career, what did a good day at work look like?

The people you work with. Music in the pumproom where we set up the heart lung machines. Sitting down for breakfast together. In the morning you get assigned to an operating room. You might have a student who is receptive to learning, you have a complicated case, but it goes well, and you get a good result. You come out of theatre, and you see yesterday’s patient who is sitting up in ICU on day one, and that was an aortic dissection you thought wouldn’t make it, and now they are sitting up and eating lunch. That’s powerful stuff. Then, in the evening, you look at the on call surgical team and you think, “Yep, if something happens at 3am, I’m happy with this lot!”

Tim with perfusionists at Union Hospital, Wuhan, China in 2019.

You’ve been involved with the associations of perfusionists in India and China, how did that come about?

Green Lane has a rich history of Indian registrars coming through the unit ever since I started. They still come and spend a couple of years here, and many of them have gone back to become world leaders in their field. So, there was a big connection with India, and I had always wanted to go there. I went to a few Indian meetings of their perfusion society. I was at one Indian perfusionists meeting, and the guest speaker got up, he had been the Mayor of Mumbai, and he looked about 100 years old. I thought he would never make it to the stage, but he got up and gave the most astonishing, charismatic talk.

Dr Shanti Patel was a union leader and had been a freedom fighter, known Gandhi, and was inspirational. I was so taken by this talk, and they have multiple sponsored awards at these events, I said to them I want to sponsor an award, called the Shanti Patel award. So, after six months of negotiations with Dr Patel and his family, they agreed to me sponsoring the Dr Shanti Patel – Freedom Fighter Award, for an Indian perfusionist every year.

The China connection came about from a friend from UCLA medical centre, we got involved in myocardial protection during heart surgery using blood cardioplegia designed by Dr Gerald Buckberg, the father of blood cardioplegia. He worked out of UCLA and came out to Green Lane, and I used to go to UCLA regularly and hang out with him and his chief perfusionist Christine Cushen. Christine put me on to Dr Long Cun from Fu Wai University Hospital in China, because she said Dr Long is looking for someone to give some lectures. This would have been in 1999.

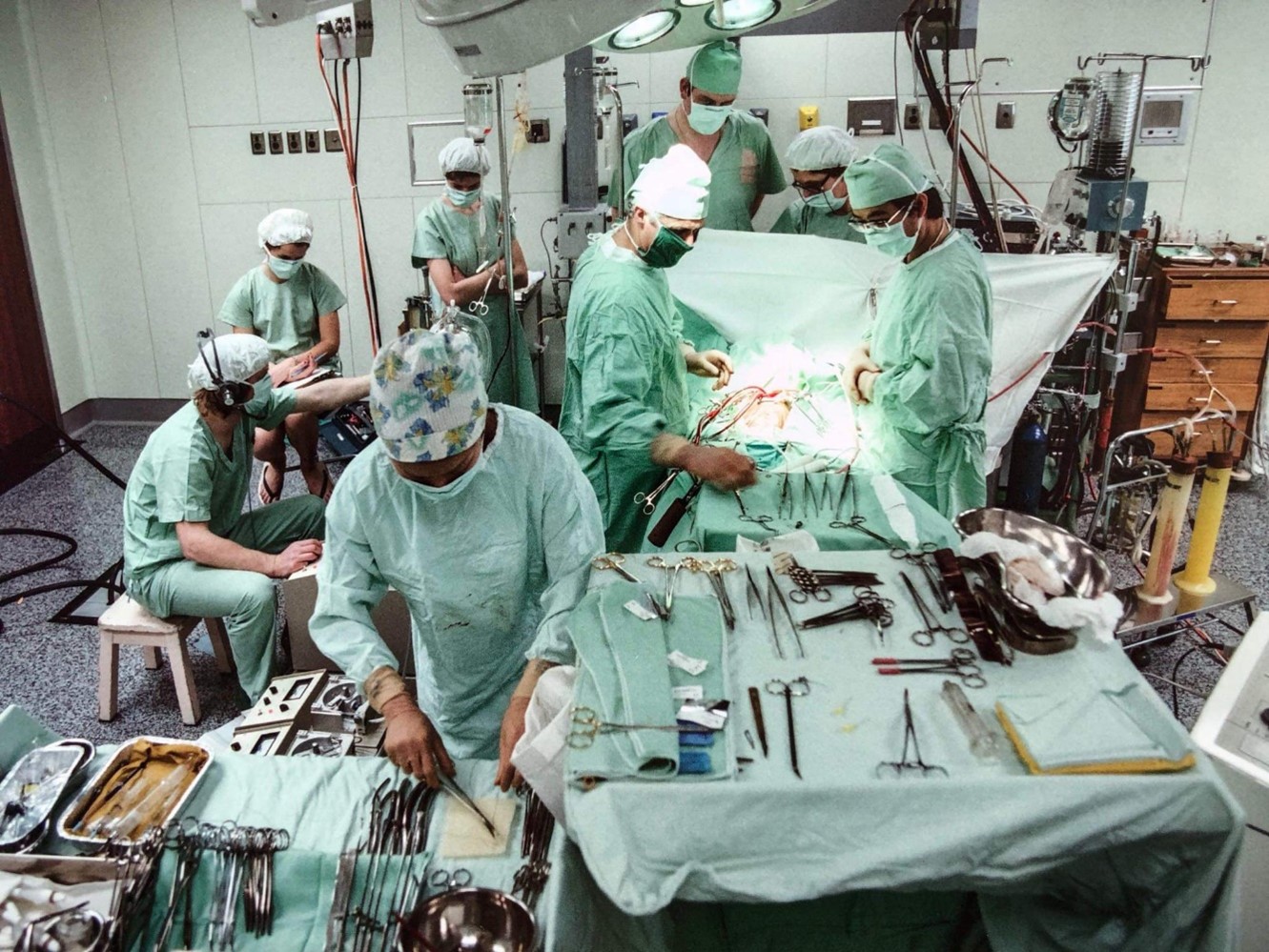

When I visited, they were using gear like we were using when I started at Green Lane in the 1970s. I kept going back, and got on with them well. During my lecture tours I would give three lectures in multiple hospitals, in five different cities, on various aspects of cardiopulmonary bypass, like myocardial protection, and more latterly, about ECMO and ECMO transport. All done in carousel slides, which were translated into Chinese. I would talk to a slide, and then Dr Long would translate it into Chinese. We were talking to whole cardiac teams about various aspects of bypass and New Zealand innovations. I would go to Chinese scientific meetings and be the only European in those early days. Their thirst for knowledge was fantastic, and they were very hospitable. Since then, there has been an exponential increase in technology there, and they’ve caught up and surpassed us now. Not just in perfusion, but in all their technology. The recognition award I got for perfusion in China is perhaps my most treasured.

What other things have you learned over the course of your career?

I became very interested in patient safety from a perfusion perspective, and I set up and run the ANZCP Perfusion Improvement Reporting Scheme since 2004. It’s a voluntary, open access, world first incident reporting scheme. It’s been going for 20 years, and records equipment and clinical errors. We look at incidents through a Safety2 lens. Looking at incidents for what went right. Something went right to prevent a worse outcome happening. We are interested in near miss data, and learning what people did right to resolve a problem, and what innovative things they did. Those incidents come through to me as editor, and are deidentified and go into a database. If permission to publish is given, they get published on the web and sent out to a group of 300 subscribers, mostly in Australia and NZ, but also around the world. People read these reports and learn from them.

The WHO’s sign in, time out, sign out checklist has made a real difference to the way we approach the operation. The surgeon will talk about his plan during time out – that was unheard of in the early days. Getting patients through safely has improved.

I have a slightly jaundiced view of management. They are there to provide us the tools to do our work – to listen to the way clinicians would most appropriately get things through and make it happen in effective way. That’s not always the way it works, and there is a lot of reinventing the wheel over the decades, as you can imagine. Health in New Zealand is at a difficult point at the moment.

What was your involvement in the Pacific?

There had been other heart surgery done in Samoa, but not using heart/lung machines and open-heart surgery. In 2006 Dr Benjamin and Dr Parma Nand decided to take a team in. I was the logistics guy. This was the first time for bypass surgery in the old TTM hospital. We had petrol generators for when the power cut off. The preparation for this took two years to organize – a team of 40 people, crates of gear. Since then, teams have regularly gone to Fiji as well.

When did you start moving up to being chief perfusionist?

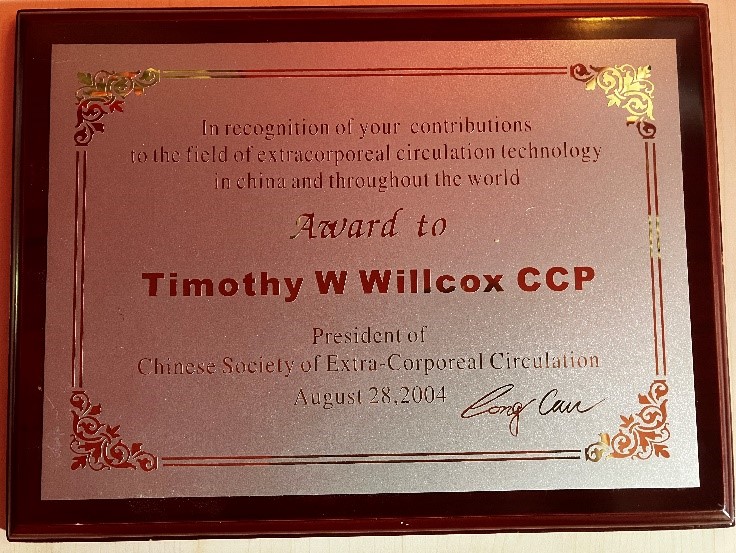

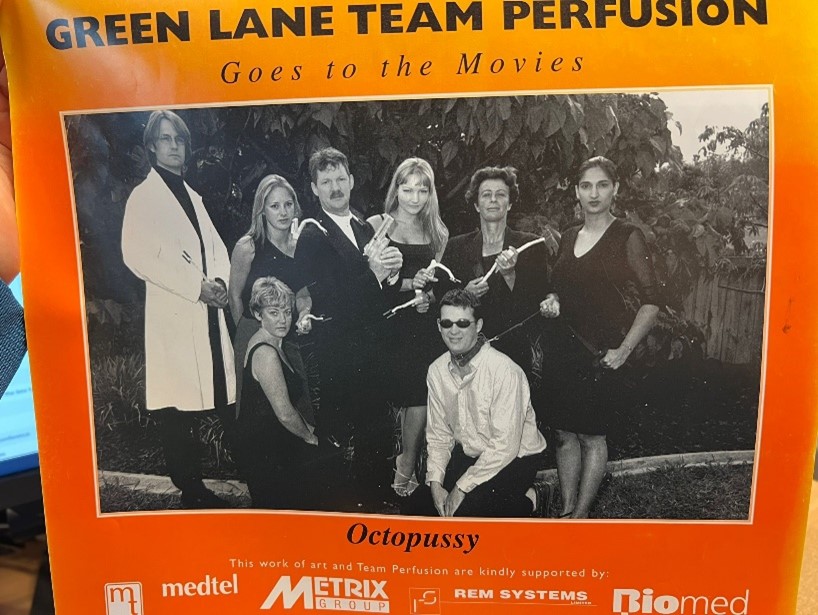

I was fairly ambitious and when the former chief left, I became chief in 1976. I had things to do! We had a small team of perfusionists and assistants who kept all the records. In those days we still had anaesthetists who knew how to run the heart/lung machine. Since then, it’s all been devolved to perfusionists, and microprocessors in the machines keep the records. We had a tight team; we made a calendar for two successive years. We were quite entrepreneurial. There were no refreshments on the floor, so we put a Coke machine in the tearoom and got the money for it. We did fun runs with the heart lung machine.

With Dr Girinath M R, head of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai.

Why are you retiring now?

People asked, “when are you going to retire?”. The current generation probably don’t see themselves as being in a single job for fifty years. That’s a different perspective, but I could dictate my own direction, and was able to have a very well-rounded career. I think it’s more restrictive now. There has to be an environment which is rich in research, with mentors who are going to bring you through. The focus is so geared to production and people want to go home, not stay at work doing crazy experiments like Simon and I did, fuelled by pizza and wine. It used to be quite fun, but it’s very serious now – with staff shortages and acuity; perfusion is now very busy. The on call is onerous, especially at Auckland, with the ECMO retrievals, retrieving hearts in a box brought back on a mini-perfusion system, rather than in cold storage, and the liver service routinely using a liver assist device which involves perfusion. And ECMO has taken off. ECMO retrieval is good sport, it’s life on the edge. Doing acute work in the middle of the night is great fun.

In the early years we would work all night on acute cases, then do the elective case the next morning. We would be operating for 30 hours straight. My wife Brigid was a cardiac scrub nurse before she became a lawyer, and did a master’s thesis on fatigue and error in the cardiac operating room, measuring fatigue and errors in surgeons and nurses. That changed practice. Nowadays surgeons who work after midnight won’t come in the next day. In those days that was unheard of. We have 12-hour breaks after call back, which is good, as I don’t think 9-hour breaks are enough.

The thing which sustains us are interests other than clinical. Mine was research, and more latterly, trekking in Nepal, beekeeping, and the gym.

I would say in answer to the retirement question, “when I stop enjoying it”. I’ve genuinely enjoyed it, and we were in Nepal at 4800 metres trekking, and I had an epiphany moment and I thought “I think it’s time to stop”. I had Wi-Fi, so I sent an email saying I’m stopping in 12 months. For the 12 months up to retirement, I did only occasional calls, which although it was where the exciting stuff happens, it was a freedom to give that up.

How did you become involved with APEX?

We were on Individual Employment Agreements which had limits to progressing our conditions. We needed expertise in terms of someone who could negotiate. APEX was suited to niche professions, it seemed to us. You guys took an interest in us, and it’s worked out well. In terms of the onerous nature of the job and the clinical responsibility. The perfusionist has got someone’s heart stopped, and you are their circulation and their heart and lungs for several hours, sometimes longer, and it needs conditions of work and remuneration that are appropriate for that, and an organization to achieve that in difficult times. With a national perfusion collective agreement, we are seeing the fruits of that.

We are also looking forward finally to registration under the HPCA, which we expect to be signed off by Cabinet in March. We are the only profession in the operating room without registration. We will come under the Medical Sciences Council. It would have been a nice box to tick before retirement, but it’s so close now.

What will you enjoy in retirement?

I’ll keep editing the incident reporting scheme, and I’m involved in a research project surveying perfusion practice in Australia and New Zealand. Professor Rob Baker and I did it 20 years ago in 2003, and we are doing a 20-year update which is fascinating. We will compare and contrast with 20 years ago, and compare with the Americans as well. I’m going to the AMSECT scientific meeting in March, in the United States, which will probably be my last.

There’s more hiking to do; we will go back to Nepal next year, as we are involved with a Sherpa family over there, as well as hobbies like bee keeping.

With the ECMO machine on an air ambulance.

Any final thoughts?

I was very fortunate to get into a profession in its infancy. Right place, right time. It’s so important to have really good mentors, and when a door opens, jump through it. It’s a matter of grabbing opportunity. I’d do it all again, exactly the same.

But it’s something of an indictment on the current state of Health NZ, that 54 years with ADHB ended last Friday without any communication whatsoever from management. It’s like I never worked there. A true measure of impermanence.